Over one hundred days after setting foot on a flat Texas highway at dawn, a group of Buddhist monks arrived on the periphery of Washington, D.C., the sunny saffron of their robes unmistakable against the city’s grayscale backdrop of snow and concrete. Across eight states, they had walked through small towns and state capitals, offering a simple gift to witnesses of their journey: a reminder that peace transcends policy and protest—and is accessible to all as a contemplative way of being in the world.

This Walk for Peace—neither branded as protest nor staged as performance, but undertaken as pilgrimage—culminated Tuesday, February 10th, 2026, with an interfaith service held at Washington National Cathedral. The monks (or bhantes, as they are known in Pali) were joined by the dean of the cathedral, Reverend Randy Hollerith, and Bishop Mariann Budde—the latter of whom many will remember for the stirring plea for mercy she voiced before President Donald Trump following his 2025 inauguration. In a season marked by political malaise and collective exhaustion, during an unusually hard winter that has beleaguered the Southern states that served as the monks’ stepping stones, their presence in the nation’s capital feels almost disorientingly gentle.

As long as the 2,300-mile distance traveled was, longer still is the tradition of the peace walk. As the monks entered the District, their robes and accoutrements swaying from their bodies as they moved in unhurried procession, the layers of whispering cloth echoed back to the Dhammayietra, the peace walks of Cambodia that saw monks and laypeople cross mine-scarred land in the hope of collective healing. In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi led the Salt March, a 240-mile nonviolent protest against British salt taxes in colonial India. This act of walking as resistance or moral witness helped define the concept of satyagraha (“truth-force”) that influenced later movements for civil rights and justice around the world. And in the United States, the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965 similarly used sustained walking to demand voting rights for African Americans. Over the course of three weeks, hundreds of advocates—guided by leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—made their way from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital in Montgomery, helping catalyze the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

The Walk for Peace undertaken by the monks of Hương Đạo Vipassana Bhavana Center resisted nothing and demanded nothing. Instead, on the evening of February 11th, it compelled thousands of people to gather outside George Washington University’s Charles E. Smith Center for a loving-kindness meditation, the final public event before the Walk for Peace would officially conclude. There are few venues more contrary to the purpose of such a meditation than a sports arena, a place built to host symbolic enactments of war, on a campus that thrums with policy debates and political ambition. Here, of all places, the monks would proffer the idea that embodied solidarity—walking together—can summon attention, shift hearts, and create space for connection, even in a time characterized by thorough division.

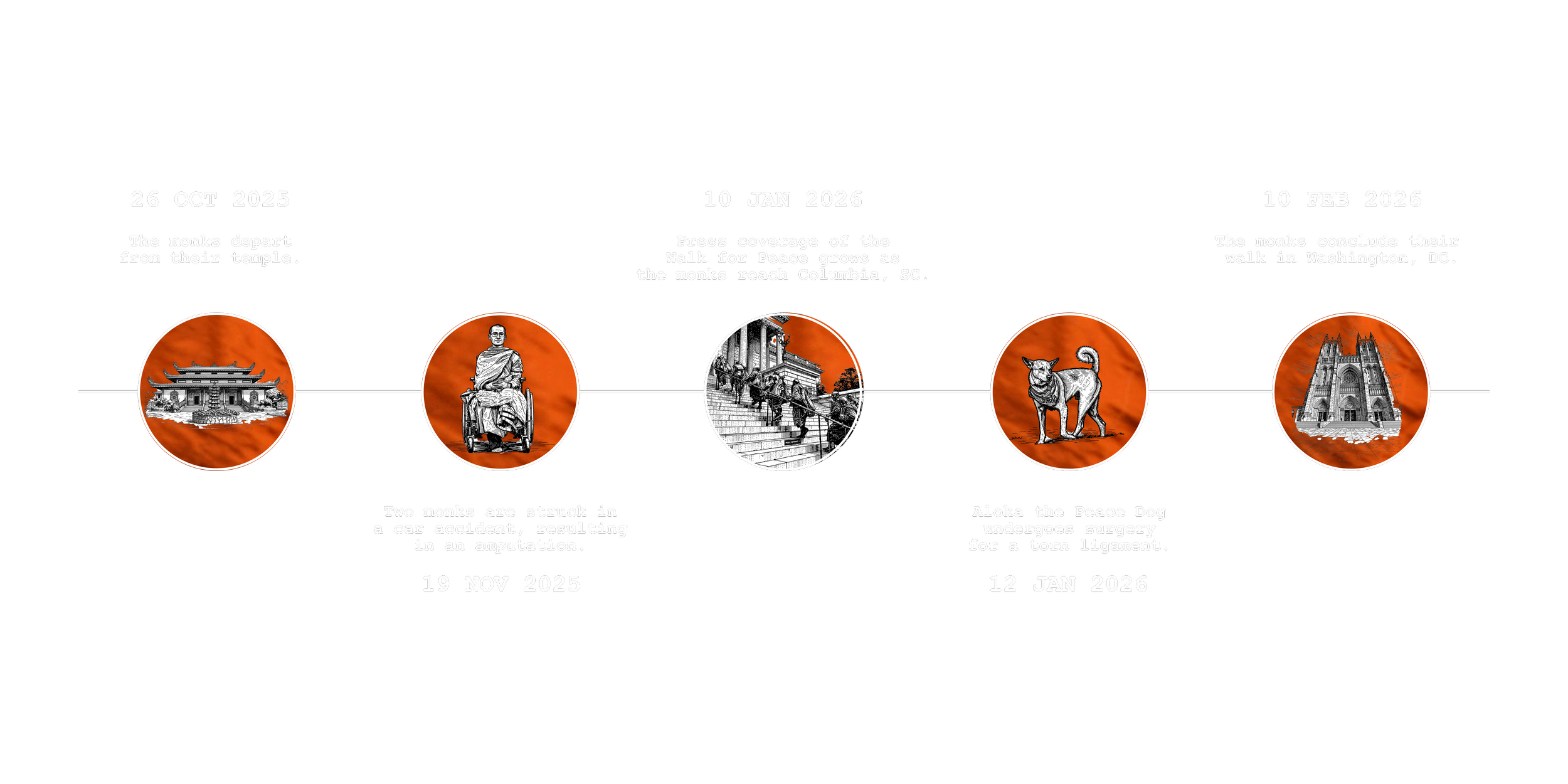

Much had happened since the monks began their trek on October 26th, 2025, just one month after the President rebranded the Department of State as the Department of War. We had suffered the loss of civilians Keith Porter, Renee Nicole Good, and Alex Pretti at the hands of masked ICE agents, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, remained besieged. Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro had been kidnapped by the U.S. military. Over a thousand immigrants had been deported daily without due process. The institutions and allyships that once helped our world feel safe, secure, and capable of progress had been crippled and some, such as USAID and soon perhaps the Department of Education, eliminated. Anxiety and distrust continue to more accurately describe the national mood than do care and cooperation. Yet there stood scores of students, city-dwellers, and visitors in a serpentine line, blanketed by the chilly shadow of the sports arena, a palpable hunger for hope hanging alongside the steam of our breath in the air.

I overheard the college students behind me chatting about their Galentine’s preparations for the upcoming holiday weekend, peppering the conversation with wisdom offered by the monks the day prior, “telling us to be kind and spiritual shit.” (“I took a picture of them getting Panera. Are they allowed to do that?”)

The elderly woman in front of me with the broad grin and wispy shoulder-length hair shared how she had been following the monks’ progress since last October, having joined for the National Cathedral service the day before and having taken the train that day, her birthday, to be here with them again. We shared a fondness for the monks’ dog Aloka—now fully recovered from the torn ligament he suffered in January—whose calm presence had become a companionable emblem of the Walk.

With his hands in his pockets and a grey beanie atop his head, the stubbled, soft-voiced young man further up the line mentioned that he grew up in a spiritual tradition that centered meditation and was involved with some of the local sanghas. Naturally, this was an event he couldn’t miss.

The queue felt about the same as any queue would, with mild, mostly good-humored annoyance emerging among the bundled-up crowd donning their earmuffs and wool scarves in the 30-degree shade, eager to move forward. Patience may have been in meager supply, but smiles—as well as flowers brought as offerings—were plenty.

After an hour of waiting, my husband and I made our way through the entrance and filed into a row situated stage-left, allowing us to gaze downward into the arena at the lucky few—mostly press and visiting Buddhist monks and nuns—who were seated directly in front of the for-then empty stage. Before the event’s end, the arena—built to hold up to 5,000 people—would be more or less at capacity. When the monks began to ascend the stage, everyone stood. Having lost his leg just over two weeks into the Walk when a vehicle collision on a two-lane road forced an emergency amputation, the wheelchair-bound Bhante Dam Phommasan was elevated via a hand-cranked lift to be reunited with his fellow monks onstage.

Opening comments from the university’s Interim Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, John Lach, reminded us of the Walk’s core message: “Peace is not only an aspiration but a daily practice.” And with that, the Walk’s leader, Venerable Bhikkhu Paññākāra, approached the podium. His robe was adorned with badges and pins given by law enforcement officers, first responders, and government officials throughout the monks’ journey, each symbolizing a gesture of mutual respect. Together, they formed a living tapestry of interfaith and intercultural cooperation, a powerful visual testimony in a climate of increasing polarization. Venerable Bhikkhu Paññākāra then led us, an audience thousands-strong, in a loving-kindness meditation. As is often the case when translating concepts across not only languages but also religious traditions, much is lost. In the hope of bringing nearer to completeness the reader’s understanding of what is meant by loving-kindness (or metta, in the original Pali), I offer this flurry of phrases: benevolence, goodwill, and (my favorite) “growing fat with friendliness.” An imperfect Western parallel would be agape.

The condensed meditation, chanted internally in this particular context, went as follows:

May I be free from resentment and conflict.

May I be free from physical suffering.

May I be free from mental suffering.

May I be free from danger.

May my body and mind be at peace.

We silently recited this to ourselves for 30 minutes before turning our attention outwards for the next half-hour:

May all beings be free from resentment and conflict.

May all beings be free from physical suffering.

May all beings be free from mental suffering.

May all beings be free from danger.

May their bodies and minds be at peace.

The first 15 minutes of this experience was deliciously transcendent. So thick with quiet was the arena that it is no exaggeration to say that you could hear a pin drop—and a car honk, a passerby shout, and a security officer’s metal-detecting wand beep as it skimmed over latecomers outside the arena doors. But for those first 15 minutes, even these sounds registered as nothing more and nothing less than the audible pulse of a living world. A sense of warmth and commonality of purpose enveloped the arena, and the line between my ending and my neighbor’s beginning blurred.

A few years of Quaker practice had prepared me well for that first quarter-hour, but then my resolve (though never fully toppled) began to show cracks. The nonstop whispering of two women behind me made freeing myself of resentment a challenge. As my shoulders grew sore from extended sitting, I was no longer free from physical suffering. Anxiety rose in me when I heard the sporadic yelling outside. I did not feel fully free from danger. My body and mind grew restless. When my eyes fluttered open periodically, I could see I was not alone in my struggle. A pair of friends exchanged a quizzical glance for a furrowed brow before leaving the arena. Many more followed suit as the meditation was ongoing. Perhaps they had been expecting more of a spectacle, rather than this immersion in the no-frills yet deeply numinous act of being present. Perhaps they had other worthy obligations to attend to. I let the first, less forgiving thought go and chose to lend the early departers the grace of the latter assumption.

It was then fitting that Venerable Bhikkhu Paññākāra should close this meditation with no grand manifesto but by stating simply that if we dedicate ourselves to wrestling with our own minds, the need to fight for peace, as though it were a prize external to ourselves, diminishes. It turns out that the dissolution of barriers—between self and not-self—that I sensed in those first 15 minutes of meditating were, at least partially, the point. If we can accomplish the hard work of settling the muddy waters of our own minds so that we can see (and feel) the peace we hold within us, this accomplishment enables others to do the same. In the monks’ own words, “Our walking itself cannot create peace. But when someone encounters us—whether by the roadside, online, or through a friend—when our message touches something deep within them, when it awakens the peace that has always lived quietly in their own heart—something sacred begins to unfold.” As transformative as laypeople’s encounters with the monks have been, Venerable Bhikkhu Paññākāra made it clear that this power is one we wield as well, sharing that he was moved to tears when seeing the crowd that had gathered for the monks’ earlier service at the Lincoln Memorial.

In a world that constantly assaults our senses and demands our attention—buy now, act now, don’t wait—finding clarity and calm is nothing short of a Herculean feat. However, Venerable Bhikkhu Paññākāra cautioned us against allowing the seeming impossibility of this task to discourage us from trying: “We just have to take our time, utilize it…make our life beautiful, make our life usable every day, and do something to cultivate some merit for yourself that you can carry with you in this journey.” Furthermore, the loving-kindness meditation was honored for the effort it takes as we were led in closing it by thrice chanting sadhu—in English, “I rejoice with this meritorious deed.” As the monks ended the event by handing out bracelets handwoven from yellow and orange threads reminiscent of their robes, they reminded us that peace isn’t solely a geopolitical concept to be argued in chambers and courts; it is a moment-by-moment practice rooted in attention, presence, and care for the whole community. Peace, thus framed, becomes less a destination than a practice carried in the body, step after step after step.

With President Trump’s first Board of Peace meeting scheduled for February 19th, seven days after the monks’ departure from Washington, D.C., one can only hope that this meditation will have ripple effects. Color me a cautiously optimistic skeptic, but one thing I do know is that, upon the monks’ arrival in the nation’s capital, even the stubborn snow from late January’s storm at last began to melt.

Peace as Practice: Lessons from the Walk for Peace